- filed under: Risky Play Resources

Risky Play With Tools In Schools

For generations, the use of tools was a rite of passage and a normal part of any child’s growth and development. Somewhere along the way, perhaps because of our focus on academics over trades, the use of real tools for real work has become an all but rare occurrence in most children’s daily lives.

What is lost when we remove the use of sometimes dangerous tools from our children’s lives?

Risky Play With Dangerous Tools

Norwegian researcher Ellen Sandseter’s 2007 study identified 6 categories of risky play that appeal to children for their ‘thrilling’ qualities. Play with dangerous tools can vary from culture to culture. The use of power tools, farm machinery, or knives may be usual in some communities, while the use of saws and hammers may be uncommon in others. Well meaning parents have moved to curb children’s access to tools to protect them from possible injury or harm, but what is the real cost of this deprivation?

Researchers have suggested that the social and emotional implications are significant; The autonomy and sense of agency that comes from being trusted to use dangerous tools appropriately is attributed to increased resiliency and responsibility in our kids.

Still nervous about risky play? I recommend this risk re-framing tool for your consideration.

Risky Play With Tools At School

In a school setting the use of tools can be challenging because of class size. Supervision and appropriate instruction is an important prerequisite to tool play in a school setting. As teachers, we talk at length about the importance of creating classrooms where children feel safe to take risks in their writing or their maths, but we shy away from supporting or holding space for students to take risks in their physical play.

Much can be said about why we do this as teachers, and fear of litigation is surely top of mind when teachers reject risky play opportunities with their students.

RELATED POST: RISKY PLAY IN FOG

As always, children must be supervised and cared for under the guidance of a qualified and experienced educator when risk is introduced to outdoor play and learning.

I will also remind teachers that hazards are different than risks, and that it is the role of the teacher to ensure hazards are assessed and removed (or mitigated as best as possible) from the learning environment to ensure the safety of students. The level of risk a child chooses to participate in should be entirely up to the child, and children should not be coerced or forced into play situations that make them uncomfortable.

Carving Pumpkins

Examples of reasonable and still “risky” play with tools at school might include the use of knives, or other cutting tools to carve pumpkins. In my teaching practice, I introduce tool play to a small group with a gradual release of responsibility for children who have demonstrated competence. That might look like children using commercially available serrated carving tools to start, and graduating to paring knives in their pumpkin carving.

Playing With Hammers and Nails

Safety goggles are provided for tool play that may have unpredictable outcomes, like removing nails from wood. Small hammers can be purchased for children’s tool play to improve engagement. These finishing hammers are lighter and less likely to cause injury as children have better control and can more easily manage the weight of the tool. Roofing nails have the largest head, which makes for a more satisfying connection of hammer to nail for beginners.

Righty Tighty Lefty Loosey: Improves Fine Motor Skills

Recently, much attention has been paid to reports of surgical interns who struggle with fine motor skills. Lack of time with crafting and craftsmanship are blamed for young adults who have limited dexterity. Providing children with screws and screwdrivers to play with is another opportunity to reinforce the simple skill of righty tighty and lefty loosey.

Saws and other construction tools can be reasonably introduced for shelter building.

Risky Play With Tools At Home

At home, parents have more freedom to expand tool play, based simply on the increased ability to supervise. When our children were young, they were introduced to power tools for simple tasks, like pumpkin carving.

Benefits Of Risky Play With Tools

There are a number of specific skills that are developed when children are free to play and build using real tools. Besides the obvious refinement of fine motor skills, allowing children the freedom to work with real tools also improves self-control, decision making and persistence. There is a strong sense of agency that comes with the responsibility of using real tools for real work which leads to improved overall confidence.

Whittle Away

The use of knives to whittle requires some instruction and can be introduced with a vegetable peeler for a gradual release of responsibility to more dangerous tool use. This book is full of advice and child friendly whittling projects.

Weapons As Tools

As an urban Canadian, weapons are not a big part of our urban culture, but I imagine for families that have strong values around hunting, the proper use and care of those tools would fall under this category of risky play.

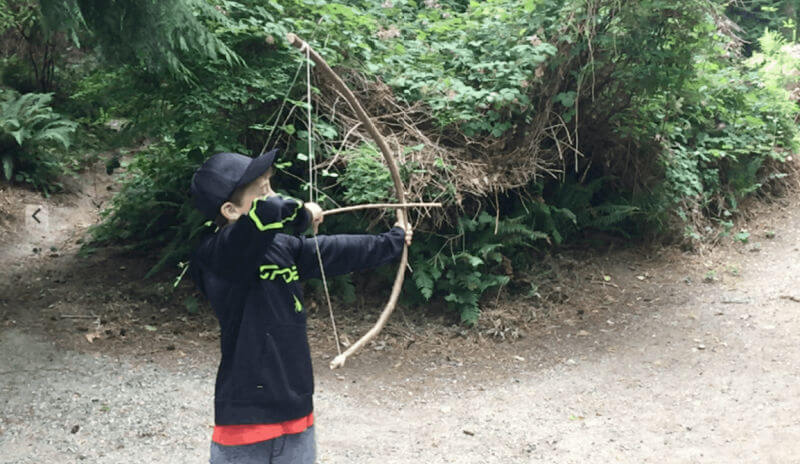

I would emphasize for children, in this context, that tools are not toys and that weapons are never to be used for play without adult supervision. For our part, on a recent camping trip, our kids designed and built their own bows and arrows from available materials in the forest. These were not used for actual hunting, but rather for playful target practice.

We live close to an uninhabited island that is a favourite spot for our family to explore during the summer months, and one of the few places our kids are free to play with their slingshot.

Of all the benefits associated with risky play outdoors, improved resilience, decision making and persistence are top of mind for me when I prepare a lesson with tool play. What are your feelings around risky tool play with children?

Want to learn more? Join me on Pinterest for curated and informative outdoor play and learning knowledge building: