- filed under: Play Research

Play Research Group: Risky Play In Schools

For our July 25 play research study group meeting, I presented slides from a presentation given at a recent Canadian Association of School System Administrators (CASSA 2019) conference sharing what opportunities for risky play in schools can look like across the province of BC. It was a conversational hour with super feedback from the group on ways to strengthen and support the sharing of knowledge with the goal of capacity building with teaching colleagues going forward.

We first unpacked what outdoor, unstructured, play might be defined as. The slide below is a result of a great deal of readings, and what I’ve landed on as the 5 characteristics of unstructured outdoor play from the literature.

I’ve done some writing on this, and am replicating a few of my thoughts here for our group.

Generations of play scholars have landed on five key characteristics of play with qualities which are consistent with unstructured outdoor play and learning: Emerging from self-determination theory, the first characteristic of play is that it is freely chosen and self-directed (King & Howard, 2016). Play scholar Peter Gray considers the ability to quit at any time a key feature of true play (2013). A second characteristic of play is that it is intrinsically motivated (Whitebread, 2018), children at play are unconcerned with rewards or the status of winning or losing. Vygotsky wrote about the third characteristic, which is the importance of play with flexible rules (and determined by the players), that leads to an ability to later abide by socially accepted norms (1978). The fourth characteristic is understood to be that play is imaginative (Huizinga, 1955) and German educator, Friedrich Froebel, wrote about the importance of imaginative play for young children to develop their sense of place within the universe (1887). And finally, that play is conducted in an alert and active state of mind (Gray, 2013) which is frequently referenced in Csikszentmihalyi’s writings as a state of ‘flow’ (1988). In the context of playful learning outdoors with loose parts, I believe Play Wales summarizes these principles effectively to form a working definition of unstructured outdoor play:

Play is a process that is freely chosen, personally directed, and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas, and interests in their own way for their own reasons (2019).

We then moved on to defining general categories of risky play in schools and discussed the potential for schools to hold space for thrilling or exciting play that is freely chosen by the participants. I shared a number of images depicting children’s risky play during school hours across the province, with some examples from the UK. A discussion on the wide ranging benefits of risky play for school aged children followed.

RELATED POST: WHAT IS RISKY PLAY?

We discussed how, in schools, restrictions on play are frequently a result of an adult’s perception of risk, rather than an actual hazard to a child. We discussed dynamic risk assessments and how they might serve to improve teachers’ abilities to supervise risky play in a way that feels less vulnerable to litigation. Ultimately, from our collective readings and experiences it seems that teachers and system leaders are afraid of the following outcomes when they allow for unstructured outdoor play in schools:

Risky Play in Schools

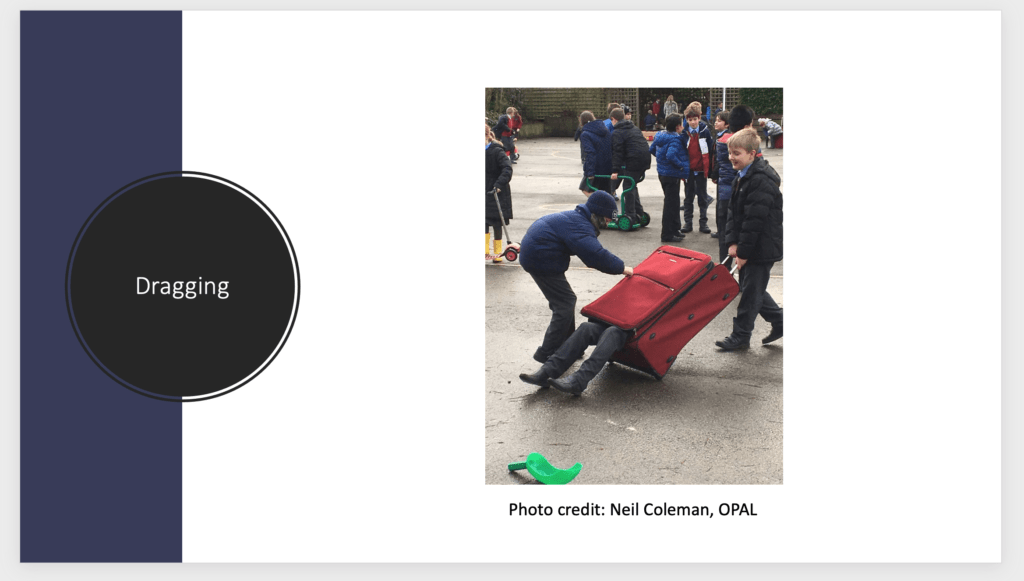

In any case, dozens of examples of what risky play can look like in schools were shared. Some selected examples are shared below. I’ve also written an entire post on the thrilling sensation of being away from direct supervision in fog play here and I’ve written about risky play with tools in schools here.

RELATED POST: RISKY PLAY IN FOG

RELATED POST: RISKY PLAY WITH TOOLS

Stay tuned for a full blog post on the essential benefits of holding space for rough and tumble play in schools! This image is from the amazing Keri and the team over at EKO-logy in the Surrey School District.

And while I can’t capture the entire conversation in this blog post, I will add one more image that gets a good laugh from everyone! A reminder to any graduate students wanting to join our study group that we meet every other Thursday on campus at UBC vancouver in the SPPH building. RSVP to Emily at [email protected]

References:

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Csikszentmihalyi, I. S., & Cambridge Core All Books. (1988). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. Cambridge;New York;: Cambridge University Press.

Froebel, F. (1887). The education of man. New York: D. Appleton.

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn: Why unleashing the instinct to play will make our children happier, more self-reliant, and better students for life. New York: Basic Books.

Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo Ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

King, P., & Howard, J. (2016). Free choice or adaptable choice: Self-determination theory and play. American Journal of Play, 9(1), 56.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Whitebread, D. (2018). Play: The new renaissance. International Journal of Play, 7(3), 237-243. doi:10.1080/21594937.2018.1532952